Like so many special encounters, this one, too, began serendipitously. To stay in the know while away on our world travels I would occasionally glance at our home town Next Door email digest. We were in COVID lockdown in Prague, when I scrolled down this particular Nextdoor email and my eyes stopped at a request from a woman in Berkeley looking for help with translating letters from Czech to English. I had translated some old letters from Slovene to English before for friends and acquaintances with ancestors from my homeland and it was very fun, interesting, and rewarding.

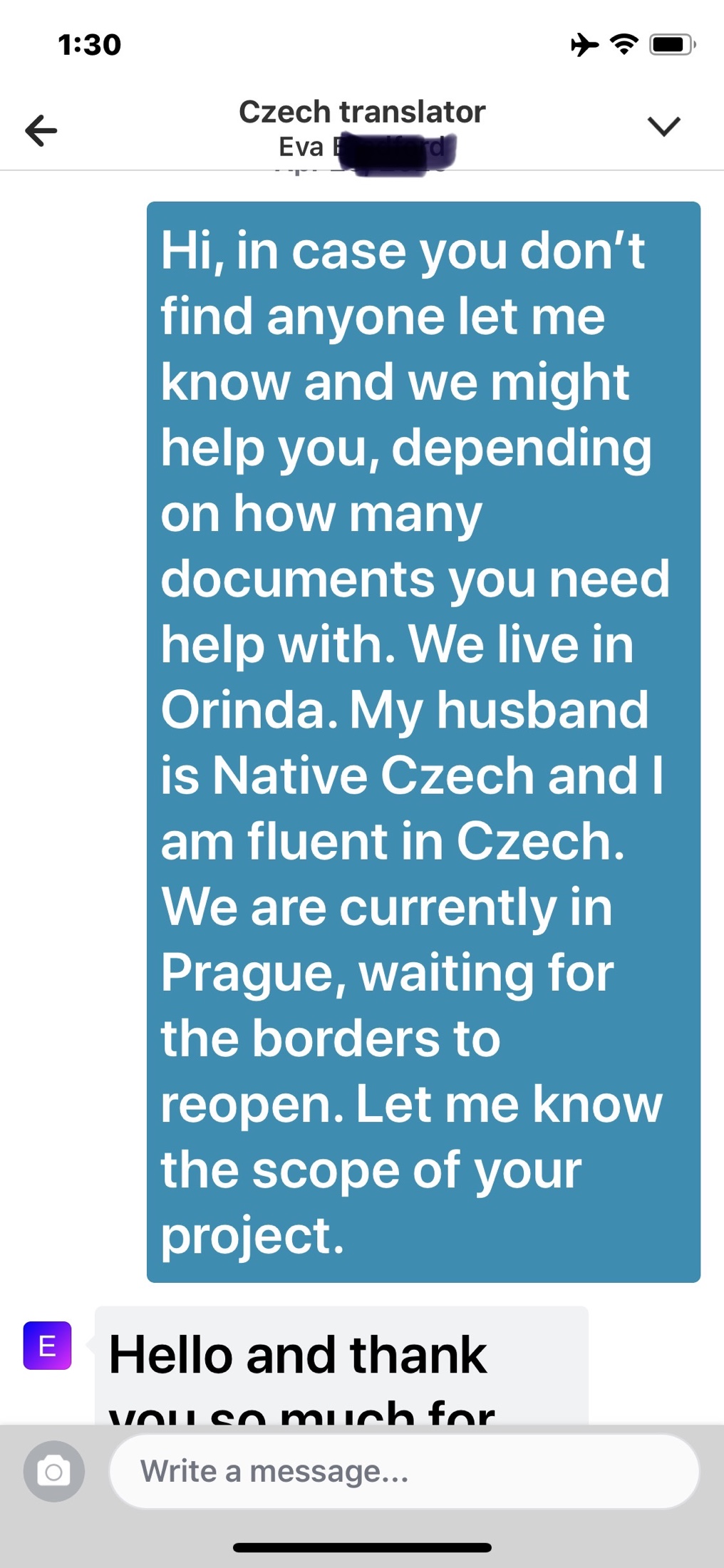

Being pretty fluent for a nonnative Czech speaker I figured I could do this with the additional help of my Czech husband. It seemed like perfect timing, too, seeing that we might be sheltering in place indefinitely. So I sent her a response:

I got a quick reaction from Eva:

”Hello and thank you so much for responding! I have sent a couple of sample letters to one person and will learn whether he is interested or not soon. However, I worked with two German translators recently and that went well. So if you are interested, we can pursue this further. I can give you an idea of the scope in the next couple of days. I have been sending scanned copies of letters/documents to the translators via email and they email me back with a Word file, so the work can be done at a distance. Although there is no deadline, I feel under time pressure due to my age so would need the translator to have sufficient time available.

Do you remain in Prague because you cannot return to the States? I thought residents are able to return. I hope you are doing all right.”

Thus our line of communication was open. I explained to Eva that I was not really a professional translator, but would volunteer to help her out.

If Eva was reluctant at first, she was forced to consider my offer, as despite posting at UC Berkeley Slavic department and elsewhere, people were not lining up to get translation work. Still, she was worried we would run out of steam as we had declined to be paid.

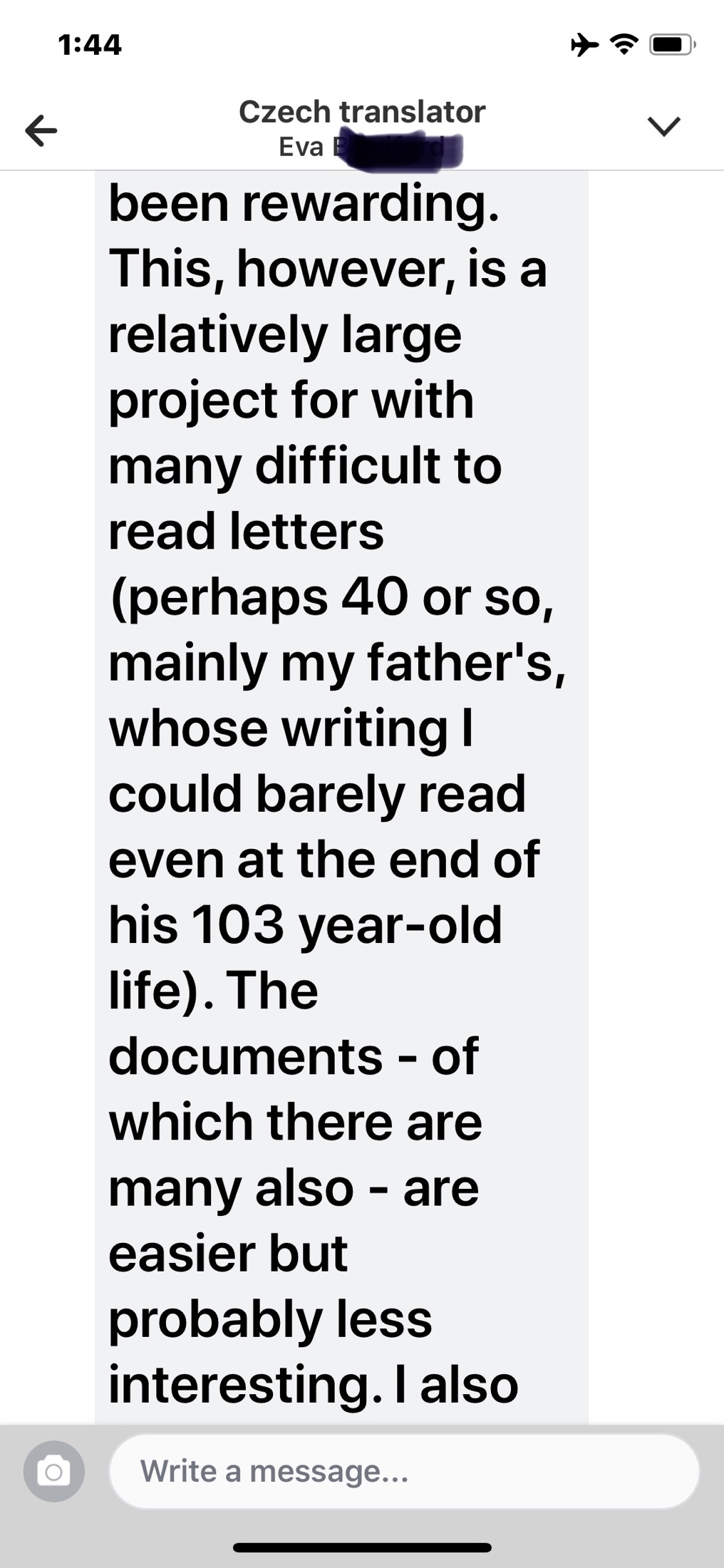

Of course she couldn’t have known our mindset and our interest in history. With every piece of information we were more intrigued. Wow, her father lived to be 103 years old. How very interesting.

Seeing that my husband was born in 1948 and lived in Prague there was another connection. ”Let’s start with one letter”, I suggested, ”and see how difficult it would be to read the handwriting.”

As soon as the first letter appeared in our inbox, we were hooked. Not only was the handwriting legible, but it was beautiful and the content heartwarming (the tough letters came later on).

At the beginning, the letters were all from Eva’s father Otto to her mother Lisa.

When Eva saw our enthusiastic response she sent us her parents’ life story, based on her parents’ autobiographies and additional testimonies she amassed, starting with her university project in 1986.

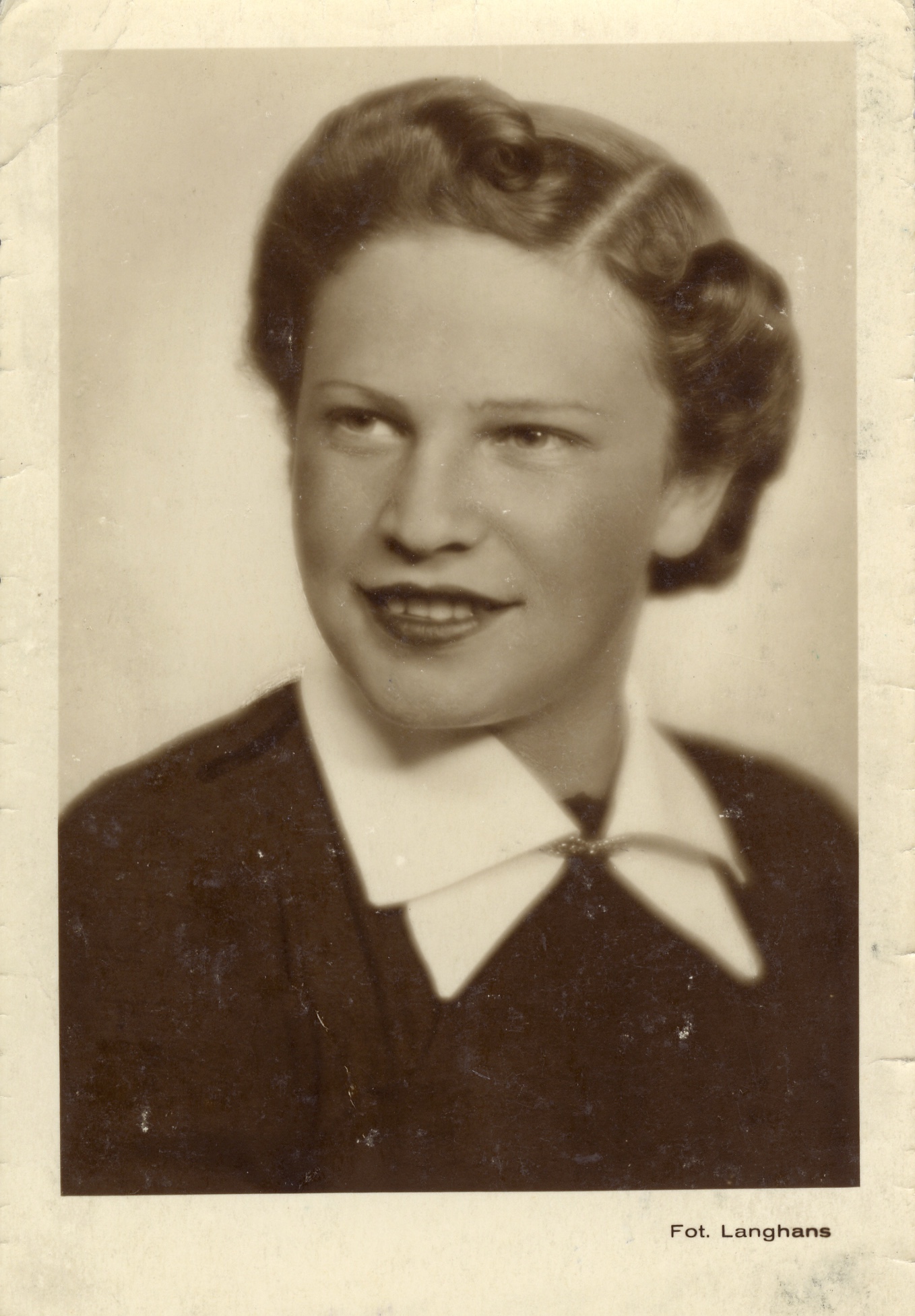

As newlyweds, in 1939 her young Jewish mother Lisa and father Otto were so very lucky to secure through an acquaintance a precious exit permit under a pretext of going on a honeymoon outside the recently German-occupied Czechoslovakia. Thus they saved themselves from the tragic fate of most of their family and friends. Sadly, the acquaintance who helped them stayed on too long and perished.

Often the question is asked, Why didn’t more Jews leave when they still could? Eva’s parents testimony gave us a personalized glimpse into the situation, the uncertainty and the rationalizations we all are prone to: It won’t be that bad, it will be over quickly, we won’t be affected. Until it is too late…

In Lisa’s words: “Everybody was following the news. The Czechs had a good army. They will fight the Germans if they want to invade. 1938 went, 1939 started. It got more and more frantic. I really don’t know what and where my feelings were. I was in love, wanted to go with Otto to the end of the world, but what do we do there, how and from what do we live? John also wanted to leave, but my father did not. “Oh, nothing is going to happen.” Will Germany invade? The Allies don’t want war! Nobody could answer all these questions. By that time I was 22, I lived a well cushioned life so far, but was I ready for life after April ’39? No, I don’t think anybody was. I didn’t want to get married because I had only known Dad for 6 months. I told my father, “If everything goes well, I promise that we will get married” but my father said, “No, you can’t go unless you are married.”

As we we were getting deeper into their lives, parallels with our lives kept coming up. As a young man Mirek witnessed the occupation of his homeland by the Soviet forces and was stuck behind the Iron Curtain in Czechoslovakia, trying to secure precious exit permits. Before our wedding Mirek and I were separated for a year and wrote letters nearly every day to each other. Those handwritten letters are saved in a big box now).

Originally Otto and Lisa were planning to go to Ecuador, the only country they could get a visa and boat tickets to, but the young couple ended up in France where Otto was assigned to the Czechoslovak Forces in exile.

When France fell to the Nazis they miraculously managed to reunite and get to England. Otto’s regiment came under the command of the British Liberation Army. Eva’s only brother and his wife also managed to escape to England, and he became a military judge in the Czechoslovak Forces. Otto felt strongly he couldn’t leave Europe because he had to fight for his family that stayed behind in Czechoslovakia, especially his three sisters. Later he was racked with doubt, thinking he might have been able to save his family and bring them to South America if only he had listened to his wife, who wanted to emigrate.

Otto had three sisters, Anna, Helena, and Olga.

Anna was single, Olga (Olly), who was trained as a nurse was engaged, and Helena (Helly) was married to a man whose father was Jewish and mother German.

Olly’s fiancé was in France and he was helping Jews get their money out. Gestapo was looking for him in Prague and when they couldn’t pick him up, they took his fiancé Olly instead. It took time and bribes to get her out.

All the war years Otto had no news about them, but he knew very well the situation for Jews in Czechoslovakia was dire.

In England Lisa found out she was pregnant, a challenging situation in such dangerous and uncertain times. For a while she could find living quarters close to where Otto was stationed but after the birth of baby Eva in 1942 they were separated.

Unfortunately none of Lisa’s many letters have been preserved, but Lisa saved all of Otto’s frequent letters.

They all start with ”My Beloved Lisinka”. He wrote letters in German and in Czech. In a letter from 1940, he utters words that many soldiers must have thought and every wife should have received.

My lines have a double purpose, a declaration of love – words that you will be happy to read – and a few words of farewell, words that arise from the thoughts of someone who is at war.

Lisele, I love you infinitely, you have given me a lot of joy and peace, you have stuck by me in good times and even more dearly in bad times. My love, you are good and brave and I am infinitely grateful to you. It is my dearest wish that you live to see better times again, that you will live happily, calmly and contentedly.

And that actually brings me to the second part of my letter. You have to live and this is actually the first time that I am demanding something from you, but it is a sacred demand. You have to live, whatever may happen.

His letters are full of longing to be with his wife and baby.

Soon the baby turns into a toddler and then a little girl. Luckily, Lisa’s sister in law has a little boy, so they find shelter together. For a while, they even rent a small house by the seaside and send happy reports to their soldier husbands. It must have been such a wonderful relief to know that your wife and child were safely away from the devastating bombing raids. In one of the letters I noticed the house address and out of curiosity looked it up on Googlemaps.

I bet the house doesn’t look so very different now.

Imagine the surprise when I sent Eva the pictures by email. I even found a photo of the beach where they went for walks on sunny days.

As the quarantine restrictions lessened we ventured out of Prague with a car and a pair of face masks.

We found out that Eva’s mom Lisa was from a small town in the Northern area of Czech Republic, close to the German border, called Sudety (Sudetenland). Historically it was inhabited by a mixed population of Germans and Czechs and many Jews. The annexation of Sudetenland (and protection of its German population) was Hitler’s excuse for occupying Czechoslovakia and de facto cause of World War II. By that time Lisa’s family has moved from her birthplace of Krásná Lípa (Shönelinden) to Prague. Her father was a sales manager in glass factories and her family lived a good life, even spending their vacations on beaches of Europe.

One early spring morning we drove to her small town and true to its name found a big linden tree on the main square.

It only just started budding with a few green leaves.

Everything except a coffee-to-go window was closed for Coronavirus. We ordered some coffee and asked the pleasant owner if she knew any Fischls (Lisa’s maiden name) or any Jewish cemetery. The answer was no on both counts, but she directed us to the church cemetery. We like wandering around cemeteries, reading the names and an occasional moving epitaph. It was especially poignant that day thinking of Lisa and her family and friends that perished.

Sadly, most Jewish cemeteries have been destroyed and not all by occupying Germans. Many were also demolished by the communists after the war.

We were surprised to find one in České Budějovice, the birthplace of Eva’s father Otto. We visited the town in the south of the Czech Republic with a whole new perspective. As we walked around the Coronavirus deserted downtown I was thinking about young Otto walking past the very same fountain 100 years ago.

He must have shown it to his new bride when as newlyweds they came to say goodbye to his parents, before their departure for their supposed honeymoon. Did it cross their mind then that they might never see each other again?

The Jewish cemetery was far out of town, and it was early evening by the time we arrived. Despite near destruction and frequent vandalism in the past it was now in a relatively good shape, protected by a wall and locked gate.

We found a note saying the key was with the doorman at the nearby factory. Mirek walked to the factory’s entrance gate and to my astonishment emerged with a key and information that the little home of the former cemetery caretaker was now a small museum.

With great effort we finally managed to open the museum’s door, barricaded by last year’s fallen leaves. Obviously very few people ever visit. Inside we found a treasure trove of photographs and information. Of course, most of it was heartbreaking. Of 1300 Jews living in the area of České Budějovice only 180 survived the war.

All in all during the Holocaust the Germans and their collaborators killed approximately 263,000 Jews in Czechoslovakia. For us those numbers now had human faces and names and terrible fates.

In the museum, we found a plan of prepaid synagogue seats from 1899 and lo and behold discovered a few Fürths, the family name of Otto.

Excitedly we sent the photos to Eva. By now we were feeling like this was a hunt for our own family members. And Eva was excited to receive the photos for she had only visited Czechoslovakia once after the Velvet Revolution and had not been to the small places we were discovering.

As we continued to drive around Czech Republic we found ourselves on May 8th, the day of liberation, in the area liberated by American forces under general Patton. Usually, on that day lively celebration are held, especially in the city of Plzeň, but because of the virus only wreaths were laid.

Otto himself came into Czechoslovakia on a tank carrier at the end of the war and was assigned to liberating American forces in Sušice, close to Plzeň. A few months before, in March, he heard that at least one member of his family survived– his sister Olly.

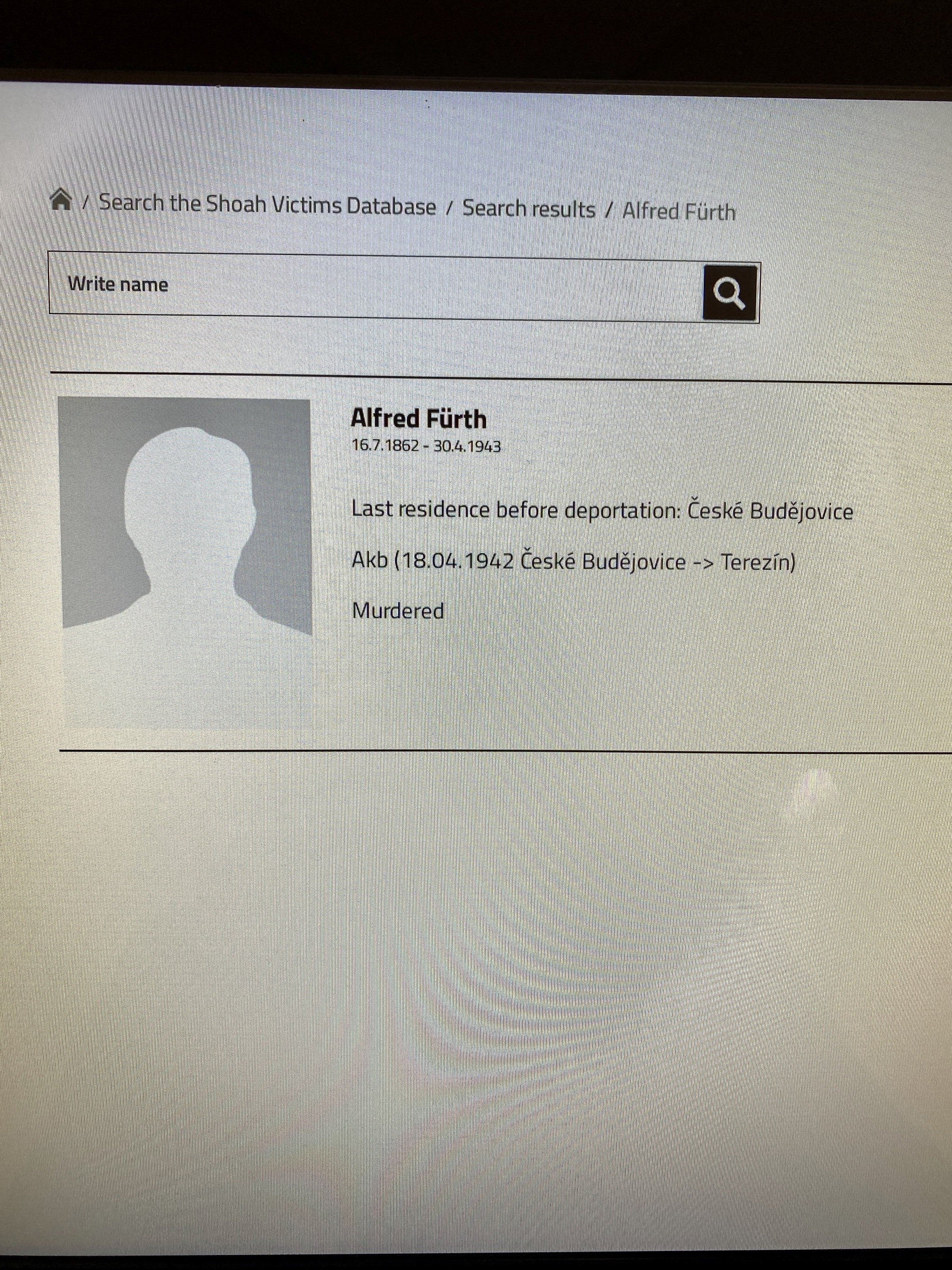

In her letter he found out that his father died in her arms in 1943 in the Terezín (Theresienstadt) concentration camp.

Terezín was a camp and a ghetto combined, and a halfway station to extermination camps for the majority of Czech Jews.

It is about an hour outside of Prague and a few times a week we would drive through the town of Terezín and past the ramparts of the camp to see our Czech grandchildren at my step daughter’s summer place – a refurbished old farm, left over from the Germans, who were all expelled after the war.

Photo credit: ecole_jaune

It is hard to imagine how could 88,000 Jewish people possibly be crammed into the small old fort. Of those 15,000 were children. As a young woman I remember seeing an exhibition of drawings and poems from children at Terezín camp titled I Never Saw Another Butterfly. It affected me deeply. Of these only 100 children lived to see a butterfly again.

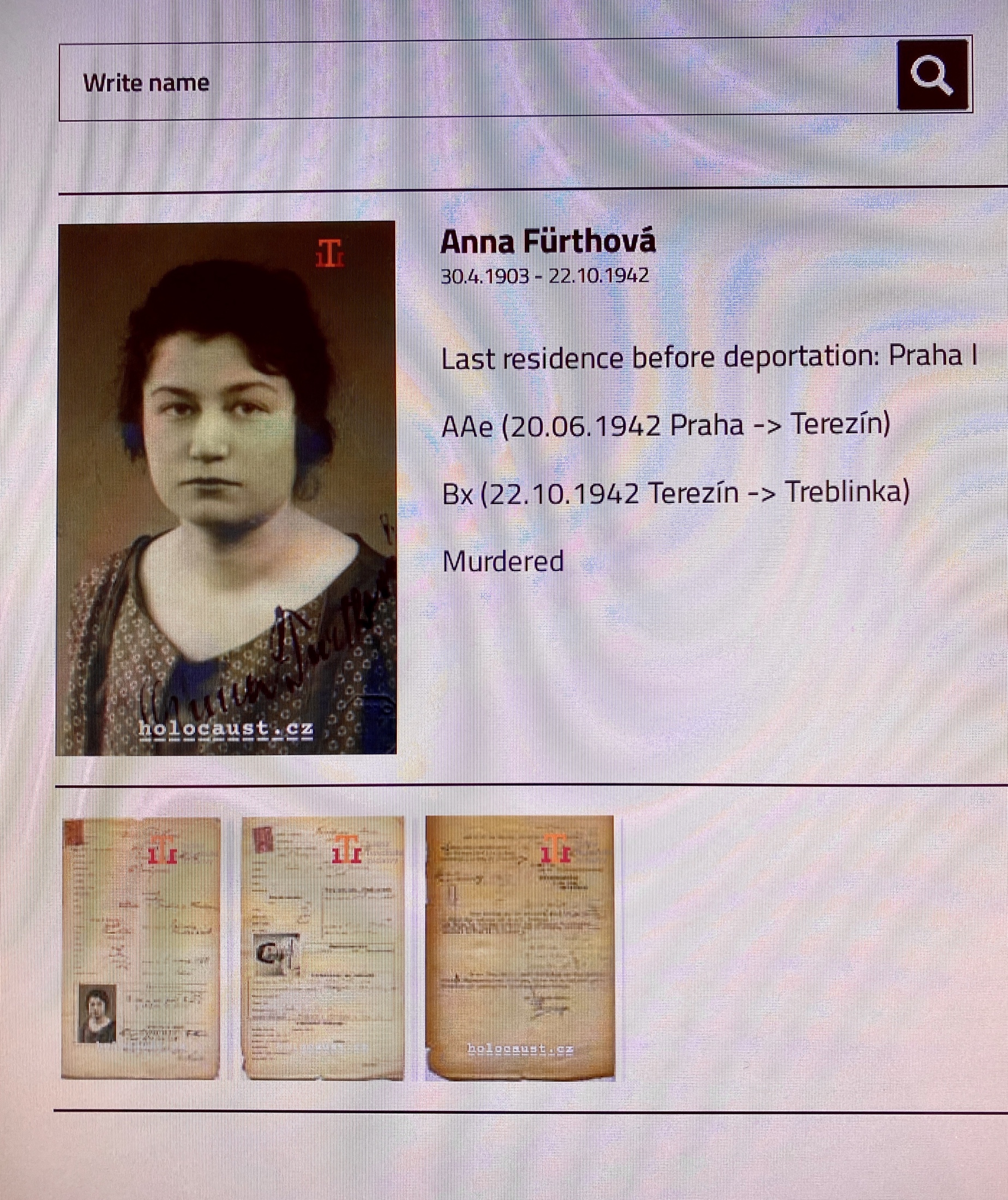

All of Otto’s sisters ended up in Terezín. Annie did not stay long and was sent to die in the gas chamber. Helly came to Terezín with her husband Peppl, who volunteered to accompany and protect her. He could have possibly saved himself not being pure Jew with his mother being German. His Jewish father was in the camp, too, and survived, but Peppl didn’t. In the fall of 1944 Helly and Peppl were separated and both taken from Terezín to Auschwitz on two different train transports. Peppl’s brother Fredy has been imprisoned there as a political prisoner from the beginning of the war. Peppl probably perished on the death march when German guards abandoned Polish Auschwitz before advancing Russian soldiers and marched the inmates in freezing January 1944 towards other camps in Germany.

His brother managed to hide in an underground bunker at the end of a tunnel he dug out with some fellow inmates and after liberation joined the freedom fighters. Helly, who was moved to and survived the Mauthausen concentration camp in Austria returned to her in-laws in Czechoslovakia weighing only 70 lbs (32 kg). Slowly recovering from typhus and malnutrition she waited in vain for her husband’s return. It was especially hard for her because his brother Fredy return a hero and married his fiancé.

Once she heard from Peppl’s fellow prisoner, most hope was lost. She wrote to her brother:

Poor Pepicek, I think I’m the only one who thinks about him, day and night. Tragically he left Oswięcim (Auschwitz) in January. The poor men were driven by those German beasts in freezing weather, poorly dressed, on foot to distant Germany. Poor Pepicek, as I learned from someone here, had his feet broken and pus-filled already in Oswięcim. When someone could not go on they simply shot him. You know I am the one who never plays theater but I am sorry to say that I have very little hope that Pepicek will return. It is all so sad. So many young people lost their lives, so few are returning, it is truly catastrophic. If I did not have you I would not want to live in this beautiful world, but I cannot cause Ollynka and you more worries and sorrow.

Olly had an incredible story of survival, too. As a nurse she had work in Terezin where she met a young doctor, who was keen on marrying her. But she was already engaged and stayed true. One after another her relatives and friends were put on train transports and nothing was heard from them. One day she was offered a spot on a transport to – Switzerland. With nobody left she agreed, not knowing where she will end. She couldn’t have known that American Jews collected a lot of money and paid Nazis, now desperate for cash, per head for rescued Jews. So indeed Olly arrived in Switzerland, where she found a way to get in touch with Otto. In every letter to him she asks about her fiancé, until she finally receives an answer directly from him. He survives the war, but his love for her does not. He is married with a child. Oh, I cried with poor Olly.

As life started returning to more normal dimensions in Prague museums reopened and we booked the first guided tour of the old Jewish cemetery

and synagogues.

It has been many many years since we have been there as those are exceedingly popular sites, always crowded with tourists and competing groups jostling for entrance.

But now we had it nearly all to ourselves and we were so lucky as to have the Director of Education Zuzana for our guide.

We had a chance to learn so much from her, and she even shared her own story. Zuzana had no idea she was Jewish until the Velvet Revolution in 1989 when her parents sat down her and her brother at the kitchen table and told them the truth. They were protecting them by withholding the information, but with communists gone they felt they could share the truth. Their family was Jewish, her grandmother a Russian Jew. Zuzana was 11 at the time and this changed her life. She went to university and later studied in Israel. She became fluent in Hebrew.

In the Jewish Museum we discovered a computer with the database of Jewish victims from Terezín. I typed in Otto’s father’s name.

Then Otto’s sister Annie’s name

It was emotional coming face to face with a person that I came to know through letters and family history.

We told Zuzana about the letters we were translating and she wanted to be introduced to Eva. And thus more strangers got connected.

So what happened after the war? Lisa and Eva flew on a stripped-down B24 bomber from London to join Otto in Prague. The reunion was sweet, but the reality bitter. Said Lisa: “One felt like living in a cemetery, every house reminded one of somebody we had known. The population (regime) on the whole was unfriendly. In the eyes of many (gentiles) only the Jews, who had not returned, were the decent ones.”

Soon Otto was decommissioned and life in post-war Czechoslovakia was not easy, especially for Jews. In 1948 the communists staged a coup and it was clear to Otto, (who refused to join the communist party) and Lisa that they needed out yet again. An interesting parallel again with Mirek, who also refused to join the communist party and got in trouble for it and that was the beginning of our road ending up in California.

The only visa they could get was to Paraguay but they deliberately missed the boat and made their way to England. With little work available in post war Britain a few years later they got a visa to United States. They settled in Chicago and they finally could get a (late) start of a new life as a family in freedom. Certainly not easy to start your life from scratch! We could relate as immigrants that came to the States with two suitcases and only enough cash to buy a (very) used car.

Olly came back to Prague from the Swiss refuge camp and started working for US Czech Joint Commission. She got over her fiancé’s betrayal and fell in love with her boss. When he fled in 1948 to Paris, she followed him. They married and emigrated to Israel.

Eventually Otto helped Helly get out to England and then even brought her to live with them in Chicago where she finally recovered and married for the second time.

I wrote to Eva if there were any relatives left in Czech Republic. ”Only indirect, ” she responded. ”Otto stayed in touch with Helly’s brother in law and his daughter Petra came to America once to visit. Let me see if her email is still valid.”

By the next morning I had another connection to a stranger that I felt I already knew somehow.

We spent a few hours on the phone and she told me many stories about her father Fredy who also lived to be over 100 years old and was involved with the Auschwitz memorial.

I was able to fill her in on what I glimpsed from the letters we translated and she told me how her father after the liberation from concentration camp fought Germans in Slovakia.

She very generously invited us to visit her and was excited to show us Olomouc, her home town. We set the date and we were very excited to meet her and her husband and then our granddaughter decided to make a month early arrival. We scrambled to change plane tickets and make it back home to California to welcome the new baby. Hopefully, on the next return to Europe, we can finish the unfinished business.

As we returned to California one of the first people I called was Eva. The voice on the other side was warm and excited and I felt like I was calling a family member I hadn’t seen in a long while. Of course, because of our strict quarantine, despite living a mere 10 minutes away, we couldn’t get together, but we spent long hours on the phone every week. We finished translating the last letters and then Eva discovered another online archive where she got the photos of the deportation cards from Terezín, which finally clarified where Anna’s last moments on earth were. It was not Auschwitz as everyone speculated, but Treblinka, another infamous extermination camp in Poland.

How chilling to stare at her death warrant…

On the card I noticed poor Annie’s last address and I remembered reading that Otto went there to hide from Gestapo before leaving Czechoslovakia. I looked it up on Google Maps and realized we walk past it often when in Prague.

It is on the most beautiful and exclusive street in Prague, where all the high-end boutiques reside.

Annie’s building now has Dolce Gabbana’s modern storefront.

Yet the gate and the light fixture are still original. In my mind I see Otto in the evening walking cautiously towards the light that is shining at the entrance. He opens the iron gate and is safe inside.

Not so the 6 million Jews that perished in the Shoah. A few of the last witnesses of those horrendous times, like Eva, that were children at the time, are amongst us. Soon only letters will remain.

What an amazing story! I was enthralled. How wonderful for Eva that you undertook the interpretation of the letters and search for her family. The other part of this story is how amazing you two are in caring for others.

LikeLike

Thank you, Margaret, we have learned so much in the process and met wonderful people and found new places. But mostly we have a new understanding of history. Sadly it now relates to our understanding of the present, too. The rise of present totalitarianism especially. Are we on the cusp and when is it too late for us to flee? Are we deluding ourselves as Jews did before Hitler took over? Scarry.

LikeLike

I ditto Margaret’s comment and add how fortunate Eva is to have found you. We are all lucky to know you both! xo Joey

LikeLike

Oh Joey, as always when one volunteers to do something one gets so much more than one gains. How lucky we could pursue such a worthwhile project while in quarantine twice now!

LikeLike

First, congrats on your new granddaughter, what a wonderful event in this year of terrible times.

Second, thank you for this post. It’s so important that we remember the past. I don’t need to tell you about how this era feels like we’re slipping into authoritarianism and the future could be very dark.

LikeLike

Sadly some people choose not to learn from the past or even deny or glorify it.

LikeLike

It is true that the tragic story of the Jews has already deeply moved us through many accounts, books or films, but to touch so closely the true story of a family caught in the midst of this collective drama makes the emotion even stronger. It is also very well narrated and I thank you for sharing it on your blog.

LikeLike

You are welcome. Isn’t it amazing that movies are still being made on this subject so long after the war? It is really hard to comprehend yet so universal a human story.

LikeLiked by 1 person

This really struck a cord in my heart and soul. Thank you for doing the translations .. some of the instance were similar to my father’s life… we need history to remind us never to disappear down the rabit hole again. sadly, many people miss the lessons completely…

LikeLike

I know your father’s war years suffering influenced your life in so many significant ways and taught your family the lessons of standing up against injustices. You are an inspiration of lessons well learned and life lived helping those less fortunate!

LikeLike

What a fortuitous connection which revealed so many interesting and enriching stories

LikeLike

Those are the best connections! Like connection to a generous Friend of a friend named Dorothy who put us up in Perth! Thank you, Dorothy! We remember this fortuitous connection

fondly!

LikeLike

Wow. I will have to reread this. You are entering the territory of historic chronicles. Keep at it!

LikeLike

For us travel to historic places has always been fascinating, as well as learning history, combining these two hopefully brings something of interest to others, too.

LikeLike

A very Moving Story. Gail

LikeLike

Thanks for reading and sympathizing.

LikeLike

Very emotional read for me. It’s very difficult to comprehend the cruelty and inhumanity of that time. Do you remember when we saw that girls work card in the antique shop in Prague with her photo inside? It is important to put faces and stories to the numbers to understand the staggering impact.

Are your love letters in English or Czech? If they are in Czech maybe that should be your next translation task!

LikeLike

I remember that Nazi work card. The girl was like 12. And our love letters are in English because we didn’t know each other’s language.

LikeLike

This is the most mesmerizing story and you are int the middle of it…What a wonderful thing you two have done for the family and then told all of us this sad but real story. I hated for the story to end….as I loved all of the family.

LikeLike

Thank you Diane for loving the family. It feels like our own!

LikeLike

Moved to tears. Thank you.

LikeLike

I don’t know if I can say I am happy about something so sad, but thank you for taking the time to read it. It was a fascinating travel through time and places and we feel very humbled and grateful for the privilege.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing such an amazing story. Makes this history so personal. You are quite impressive in your search for historic information. Thank you again!

LikeLike

Thank you Alison. We were always impressed how much Australians have done to commemorate WWI. Very moving.

LikeLike

Thank you for sharing this beautiful journey with Eva. Glad you are well and still enjoying yourselves! Hugs, Bobbie

>

LikeLike

Thanks Bobbie for coming on the journey. Looks like the only journeys we will do for a while now are down memory lane. Hope you are all well at your house.

LikeLike

Having known Eva and her family for decades, I knew the general contours of this story of fleeing, death, returning, and leaving again, and the way it resolved for Otto and Lisa in the U.S. You have created a masterful telling with photos, documents, maps, actual letters all bringing it to life which I find breathtaking. I was mesmorized, and now I look forward to reading other tellings of your journeys.

LikeLike

You are very kind, we are so glad you could glean more about your friend’s ancestors.

LikeLike

Ksenjia and Mirek, I finally read this chapter. It could be a novel or a movie, but devastatingly a tragedy. Thank you for sharing your new neighbor with all of us. I hope you drink champagne with Eva in 2021. Love, Bobbi

LikeLike

Thank you. We have only met Eva once, distantly in her garden for tea. Hopefully, 2021 brings champagne and real hugs.

LikeLike