Part I Rocking the Prehistoric Rock Art

Before “Bucket List” was a thing I put Algerian Tassili on my travel bucket list. I remember it well. I was still a teen when I cracked open my first thick Art History Book and immediately felt a visceral connection to prehistoric art. The effortless calligraphic arc of a wild animal’s back carved or painted on a cave wall was drawing me in with a strange force.

Some years later I fell in love with a man who also loved art and prehistoric art, to boot. And travel. How extraordinarily coincidental and auspicious for our future of sharing life and exploring the globe for forty years and counting.

We have chased prehistoric art in many places from well known caves in France and Spain to obscure places in Norway,

Namibia, and Indonesia.

But one site remained elusive: Tassili n’Ajjer National park in Algeria.

Algerian Civil war and threat of terrorism kept the doors firmly closed. Until it suddenly opened a crack in the spring of 2024 and we slipped in. With some trepidation and much gleeful anticipation… After such a long wait it was better and more than we had ever dreamed and hoped for.

It was also quite effortless for the extremely lucky introduction to the tourist guide and organizer extraordinaire Youssef, a Touareg man of exceptional charm, education, and ability.

Youssef is a young mechanical engineering professor with a PhD who speaks five languages fluently. Every question, every email and WhatsApp was answered with immediate precision and welcoming grace and soon a detailed plan was in place for a 15-day visit. The majority was spent in his beloved Sahara surrounding his hometown of Djanet, the rest up North on the antiquity-studded coast.

Taking into account the weather, his teaching schedule, and our family obligations we had to settle on March, not the perfect timing due to the start of Ramadan and the arrival of the first desert storms. We were determined to make it work worried that the door might slam shut again at a moment’s notice.

At the very last moment, we were faced with a Lufthansa worker’s strike and scrambled to rearrange overnight flights so we could make an early morning connection from the capital of Algiers to Djanet. Only when we spied the towering figure of Youssef in his striking blue traditional Tuareg clothes we truly believed it was happening, breathing a huge sigh of relief. From that moment on everything was smooth sailing and what a fantastic ride, indeed!

And how could it not be with a fabulous team making it happen.

It was pretty much a family affair with our driver Abbas, Youssef’s older brother, and Muhamad, his cousin. Their regular cook was spending holidays with his family so Bubba stepped in. In his regular life he was a rock guitarist and every evening he brought out his guitar and jammed around the campfire.

Our first of two desert camping trips was livened up by Muhhamad’s 4-year-old son Abbas.

If I had any misgivings about such a little boy coming along they quickly turned into a unique opportunity to observe intriguing cultural aspects of Tuareg parenting. The little boy had not a single toy with him yet he played and explored on his own all day long. He never whined or cried once.

We made it clear that our main interest was seeing as many prehistoric art sites as possible and Yousef delivered. Right from the start he made our jaws drop

and to our credit we never tired of scrambling over rocks or squeezing into canyons to see the treasures he led us to.

You see in prehistoric times Sahara used to be a lovely savanna with many animals cavorting in green fields. It is officially named the “greening” of the Sahara. It is thought to have been driven by changes in Earth’s orbital conditions, specifically Earth’s orbital precession. (yeah, I have no clue what does it mean, I just copied it from Google.)

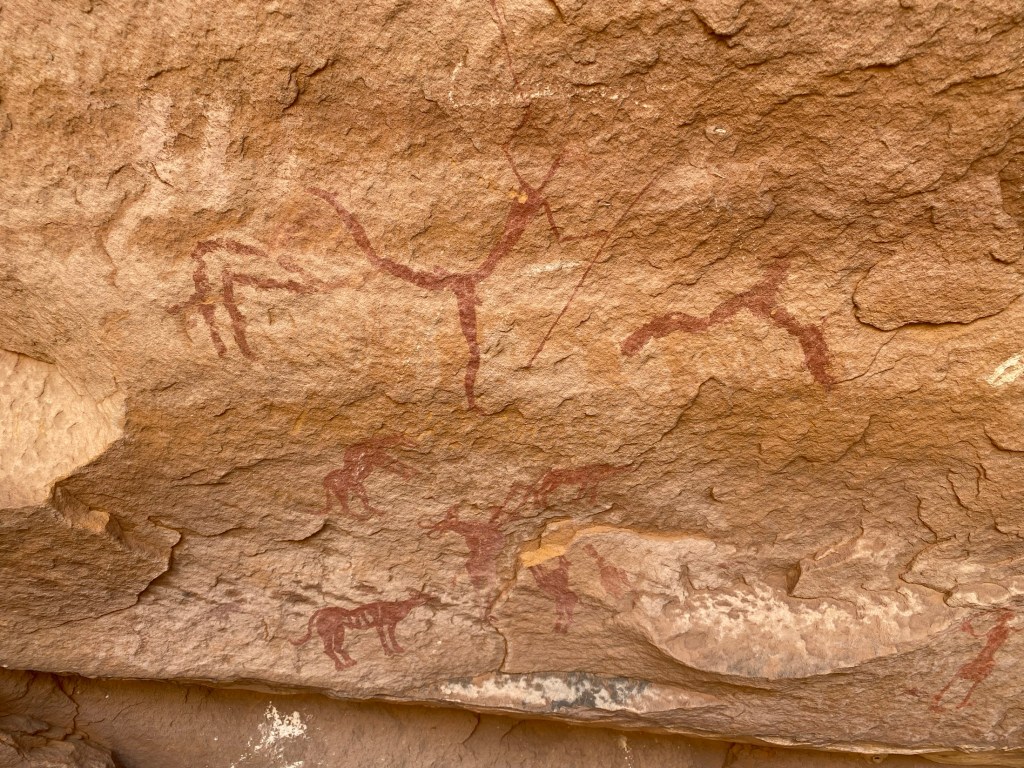

Some paintings are very well preserved, but others can be faded or layered over older paintings and images all jumbled up. The longer one looks the more details one discovers. Though at some point every red smudge on a rock’s face starts to look like a possible animal depiction.

Bands of men hunted wild animals through the ages and depicted themselves in tricolor of reds, whites, and ochers on the walls of their natural surroundings. Some pictures were very schematic but graceful nonetheless

and some incredibly realistic and detailed

And some even humoristic.

Knowing our interest in all things historic we were taken to any local (often very dusty) museum. Despite Ramadan, they magically opened their door just for us. We were treated as VIP guests and to our shock and delight invited to handle 10,000+ years old stone implements.

That is also the probable age of domestication of cattle in Africa, again beautifully depicted on the stone walls.

People turn from hunter gatherers to nomadic pastoralists with movable camps.

The long horn piebald (= multicolor) cattle are reminiscent of the cattle in Kenya or South Sudan with typical big curved horns. Some were possibly shaped by their owners like the remote Dinka tribes do till today in South Sudan.

Looking at the painting of these two herders I can’t help but think of the Mbororo or Wodaabe nomads gathering at the Gerowol courtship festival in Chad. They have the same white feathers on top of their heads and highly decorated faces and bodies.

We were lucky to visit Omo River tribes in South Ethiopia

and they still live the three dimensional colorful reality of the prehistoric life depicted in Algerian Sahara art sites.

It is interesting to see the appearance of goats, sheep, as well as domesticated dogs.

Goats are still a staple diet of the contemporary Tuareg people, the descendants of the original population of Sahara. And our main diet on this trip, too.

Later on, horses emerge and even later with the trans-Saharan trade camels make an introduction though theirs are far cruder renderings.

All in all, there have been 15,000 engravings and paintings identified to date (and more are still being discovered). Despite our best efforts, we were able to see only a teeny-tiny fraction. French archeologist Henri Lhote is credited with describing and popularizing the sites with the help of artists who copied the art onto large canvases in-situ. The exhibitions made quite a stir in France in late 1950s.

While famous European prehistoric paintings at Lascaux and Altamira caves are now closed to the public and one can only see some reproductions nearby, here you have the unique privilege of standing face to face with small and large masterpieces alike.

No lines, no timed ticket sales no nothing but Saharan sand, sun, and wind for company. Of course none of that would be at all possible without the local people’s intimate knowledge of each site and ways to get to them without a map, GPS, or road.

While “hunting” for art was an important and fun activity we often forgot all about it whilst ever-changing phantasmagoric landscapes appeared out of nowhere.

More on that in the next installment.